- Greg Mortimer, mountaineer and accidental entrepreneur, has spoken about how he created Aurora Expeditions.

- It’s an extraordinary story of business resilience

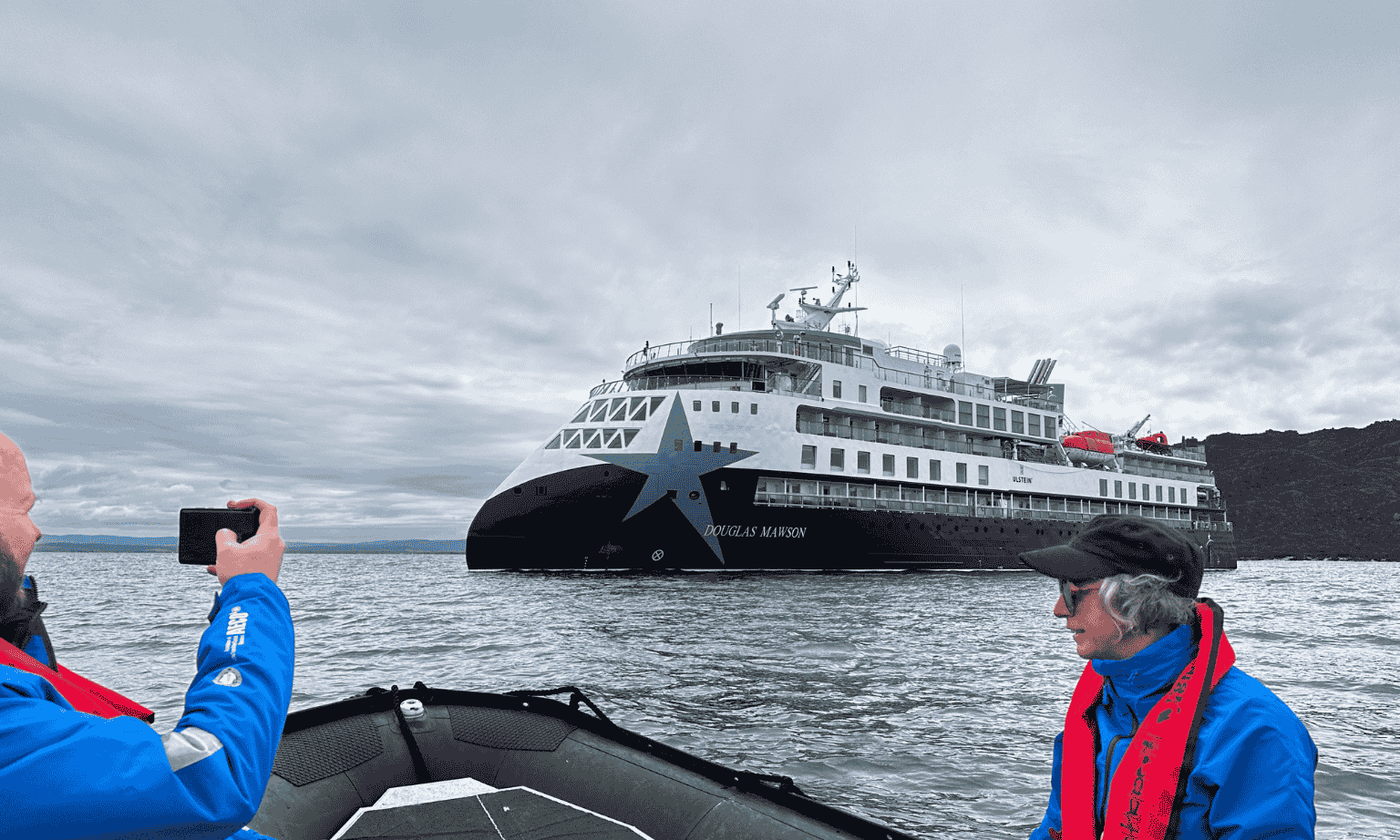

- He was talking at the inaugural of the line’s third ship. Read our review of the ship here.

The story of Aurora Expeditions begins many years before the gleaming Charles Mawson began her inaugural voyage a few weeks to the end of 2025.

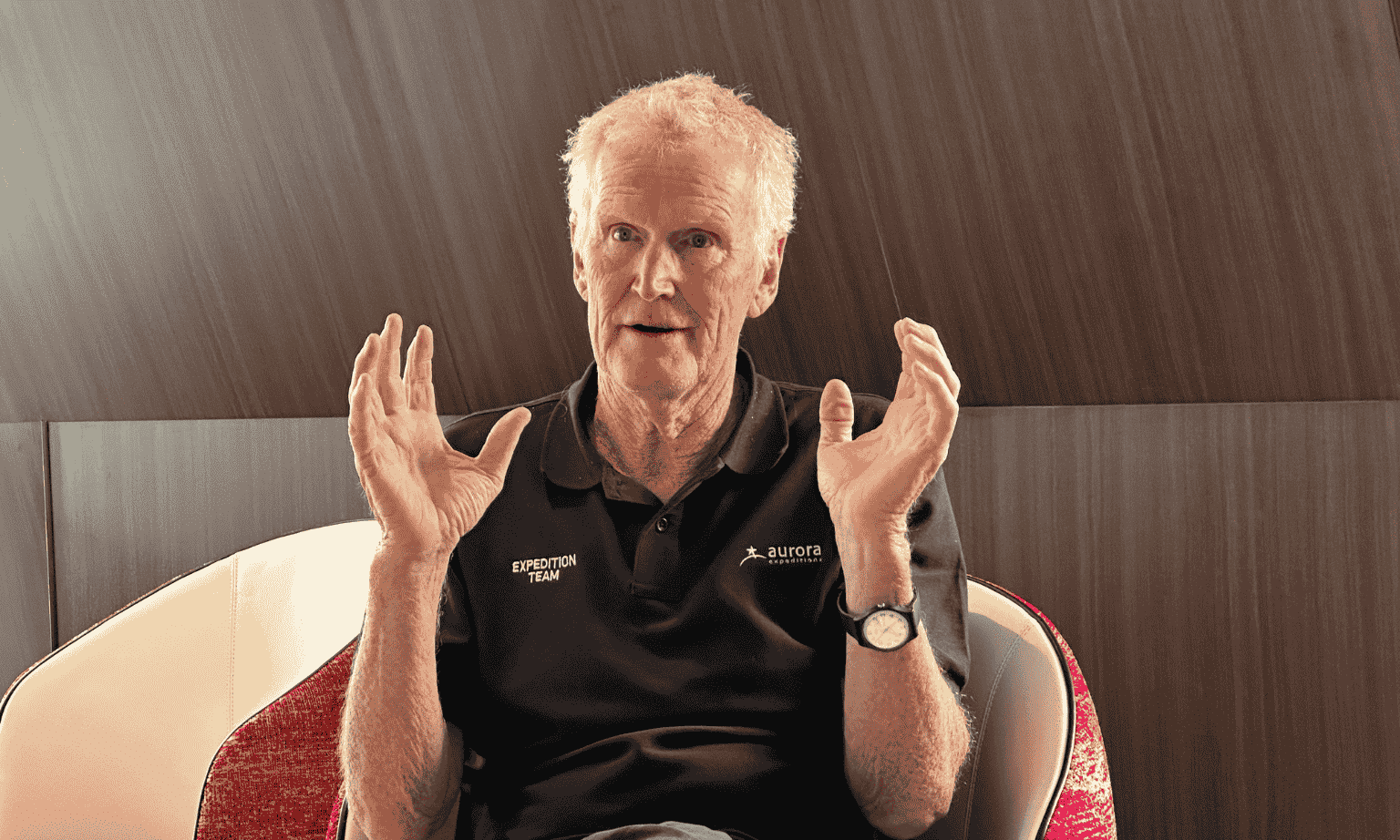

But it feels like the right time to tell the story of how Australia’s own expedition line began. In the brand new ship’s lounge sits Greg Mortimer, wearing a simple black “Expedition Team” T-shirt.

There is nothing ceremonial about him. No sense of a founder needing to be recognised or revered. He blends in seamlessly with the naturalists and guides, ducking out between sessions to join birdwatchers on the decks, seemingly as eager as any guest to spot a wandering albatross.

It is, in its way, the purest expression of the ethos he set in motion 35 years ago.

In an age where authenticity has been wrung hollow by overuse, Greg Mortimer remains the real thing — a mountaineer-turned-accidental-entrepreneur whose life’s work has been shaped not by design, but by devotion to wild places.

This is the first time he has spoken so openly about how Aurora Expeditions began, what it became, and what it must now evolve into.

View From the Top of the World

Mortimer traces everything back to the mountains. As a child, he sought out the highest points he could find. As an adult, he scaled the world’s giants. The view from those summits — humbling, disorienting, beautiful — became the lens through which he saw the world.

“When you’re above 8,000 metres,” he reflects, “you feel puny. It frames your whole understanding of the human place in nature.”

That sense of humility later defined Aurora Expeditions: voyages not engineered for luxury, but for perspective.

The story might have ended with the mountains, had it not been for another Australian adventurer: Mike McDowell, founder of Quark Expeditions and one of the first to realise that the collapse of the Soviet Union had left a fleet of ice-strengthened scientific ships suddenly available.

With a “brain the size of a planet” and a mischievous streak, McDowell recruited Mortimer for an ascent of Mount Vinson, and afterward asked him to serve as expedition leader aboard the first Russian vessel to carry tourists to Antarctica.

Mortimer had no idea what he was getting into. “I’d never done anything like it,” he laughs. “Didn’t even know what an expedition leader did. But it sounded like a great idea.”

The voyage was a revelation. On New Year’s Eve in Half Moon Bay, beneath the carved peaks of Livingston Island, passengers celebrated under the midnight sun. Music echoed across the still water.

Then, as the clock approached twelve, the captain — a former Murmansk harbour master — emerged in full ceremonial uniform. Officers lined up behind him. The boatswain appeared with a ladder, hammer, and chisel.

To the sound of Russian military music, he climbed the ladder and chiselled the hammer-and-sickle emblem off the ship’s funnel, letting it clatter into the sea.

“It was jaw-dropping,” Mortimer says. “You could feel history shifting under your feet.”

For him, the moment sparked a profound connection not only to Antarctica, but to the idea of sharing it with others.

Founding of Aurora Expeditions

When he returned home, he told his wife Margaret he wanted to take people south. No one in Australia was doing it. The very idea felt impossible. They had no money. No industry experience. Not even a business plan.

But they had passion — and a willingness to learn.

With help from World Expeditions, they learned how to ticket, roster and run trips. They built itineraries around uncertainty and discovery. And they relied shamelessly — and successfully — on “nepotism”, as Mortimer jokes.

“Friends and family — that was our wellspring.”

A rusty hull and a breakthrough voyage

Years of micro-charters eventually enabled them to book their own vessel. But the first Aurora charter almost ended before it began: the ship was four days late.

With passengers already in Ushuaia, the Mortimers improvised, distracting guests with long walks and Patagonia side trips. When the ship finally arrived, it was rusty, unmade, and not remotely ready. Greg raced out on a pilot boat to commandeer the crew.

He had them clean and paint only one side of the ship and arranged to dock on that side.

It worked. And the voyage that followed sealed Aurora’s reputation. Those first passengers became lifelong loyalists — the kind of people Aurora continues to attract: curious, adventurous, unafraid of a little chaos.

In the 1990s, Antarctic tourism was a niche run by mountain guides, explorers and outdoor educators rather than corporate conglomerates. That unusual DNA shaped the industry’s culture.

Operators were competitors, but also allies, deeply protective of the continent. Together, they built IAATO, which remains a model for collaborative stewardship.

“It’s the only continent where the rules came before the visitors,” Mortimer notes. “That’s extraordinary.”

The Aurora ethos

Listening to Mortimer speak aboard The Charles Mawson, it becomes clear that the secret to Aurora’s success isn’t marketing or scale. It’s a philosophy.

“We deliberately build in uncertainty,” he says. “We have itineraries, of course — but the magic is in not knowing exactly what each day will bring.”

That unpredictability is possible only because Aurora invests heavily in its expedition leaders: empathetic, technically skilled, hardy, and fashioned by real encounters with nature’s extremes.

“They have to come from a harsh contact with Mother Nature,” he says. “They have to know how to lead people safely in her domain.”

On Charles Mawson, Mortimer exemplifies this himself — wandering the decks with guests, pointing out seabirds. A founder who still behaves like an expedition guide.

Letting go

By 2008, after nearly two decades, the Mortimers realised Aurora wanted to grow in ways they no longer did.

“I wanted to climb mountains again,” Mortimer says. “And we didn’t have the skills to build a global company.”

They sold to new owners , including Patagonia’s former Australian distributor, who understood the brand’s soul and how to protect it even as the company expanded.

The emotions were complicated: pride, sadness, relief. Margaret especially missed the intimate relationships forged during voyages.

“You form bonds in those places,” Mortimer says. “After a while, the goodbyes become heavy.”

Still, the satisfaction of seeing Aurora become a world leader has never faded.

Today, Mortimer sees Aurora entering a third phase: one defined by environmental responsibility and real scientific partnership.

At a press briefing aboard Charles Mawson, the conversation turned to environmental footprints — a topic Mortimer treats with urgency.

“We’ve realised our passengers are a resource,” he says. “If each person we take to Antarctica went home and reduced their carbon footprint by 50 per cent, the world would change.”

The future of expedition cruising, he believes, is not just in exploring remote regions, but in empowering travellers to become environmental multipliers.

Mortimer continues to return south every year — not out of obligation, but passion. “I go down for a couple of months,” he shrugs. “There are places I still need to see.”

On Charles Mawson, watching him lean on the rail beside other expedition staff, pointing out storm petrels gliding in the ship’s slipstream, it’s clear: the fire that sparked Aurora Expeditions has never dimmed.

The company may have grown, evolved, and modernised, but curiosity and a love of nature’s most extreme corners is still guided by the man in the “Expedition Team” T-shirt, binoculars dangling from his neck, eyes fixed on the horizon.

For more on Aurora Expeditions sailings, go here.